“Nom de Guerre” is a French expression which, translated literally, means “war name”. Think “Maverick”, “Ice Man” and “Goose” in Top Gun. From a more historical perspective, think of General Thomas J. Jackson. Almost everyone calls him only by his nom de guerre: “Stonewall Jackson”. Many of our better-known military leaders have had a nom de guerre. In fact, some have had several, which reflect the relative success (at least as perceived by the public) of their military careers at the time the name is conferred.

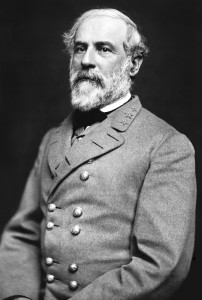

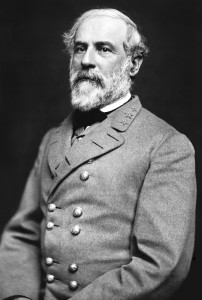

Robert E. Lee

Take for instance General Robert E. Lee. At the end of the Civil War, Lee was so venerated in the South (and pretty much in the North, too) that a small boy, learning about Lee in his classroom, asked his mother, “Momma, I’m confused. Was General Lee in the Old Testament or the New?” [1] But Lee was not always so lofty a figure in the public’s eye. At the start of the war, Lee was in charge of the disappointing Cheat Mountain Campaign in western Virginia. He was viewed by the public as being too cautious in battle, and was dubbed “Granny Lee”. After this campaign, Confederate President Jefferson Davis reassigned Lee (who had a background with the Corps of Engineers) to supervise the build-up of coastal defenses in South Carolina. This, and the construction of defensive trenches around Richmond earned Lee the sobriquet “King of Spades”, and it was not conferred in a positive tone. These early names gave way later to more positive nicknames later, after Lee’s brilliance as a field commander was established. Later we see him referred to affectionately as “Bobby Lee” and reverently as “Marse Robert” (marse is slang for master).

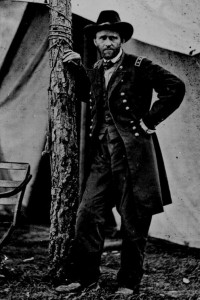

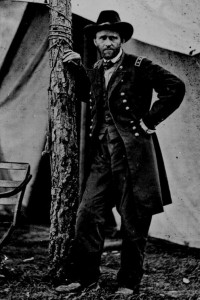

Ulysses S. Grant

And how about Lee’s nemesis, General Ulysses S. Grant? After the successful investment of Fort Donelson, Grant received a request for surrender terms from the rebel commander, Simon Bolivar Buckner. Grant’s famous reply was “No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.” [3] The capture of Fort Donelson in 1862 was one of the earliest Union successes in the Civil War, when the North was hungry for good news. The press seized upon the term “unconditional surrender”, and since it fit neatly into Grant’s initials, U.S. Grant became “Unconditional Surrender Grant”. Later, during the long and bloody campaign against Lee in 1864, when the war seemed interminable and Northern morale was flagging, Grant was nicknamed “The Butcher” or “Grant the Butcher” due to the high number of Union casualties, especially at Cold Harbor. This was not any more descriptive of Grant than “Granny Lee” was descriptive of Lee, since Grant had shown time and again during the war his care of the troops under his command. When Grant was finally able to pin Lee down and force a surrender he offered generous terms, according to Abraham Lincoln’s wishes to “let ’em up easy” and his own inclinations. After the surrender he was the “Hero of Appomattox” and once again the darling of the North.

George S. Patton

In World War II, General

George S. Patton was known as

“Old Blood and Guts” because he was the most aggressive fighting general in the European Theater. Check out his

speech to his troops upon assuming command of the Third Army just before

D-Day, and you’ll get a little insight to his approach to war. In North Africa, he squared off against a wily opponent in Germany’s

Erwin Rommel, respectfully called

“The Desert Fox” by the British. Which reminds me of the unstated rule of

noms de guerre. A regular pseudonym may be self-imposed, say for example

“Mark Twain”, which Samuel Langhorne Clemens chose to commemorate his days as a Mississippi riverboat pilot (“mark, twain” was the boatman’s call at measuring two fathoms, a minimum safe depth for navigation). Not so a

nom de guerre, which must be chosen by your friends, the soldiers under your command, the press, or perhaps by your enemy.

Sources:

[1] The History Channel Presents The Civil War, The History Channel DVD Collection

[2] Lee’s Nicknames, Son of the South

[3] Correspondence Between Ulysses S. Grant and Simon B. Buckner Discussing Surrender Terms at Ft. Donelson, CivilWarHome.com

[4] The Famous Patton Speech, by Charles M. Province