Four Famous Flags

I love the red, white and blue image of the “Stars and Stripes” against a sky-blue background. Our flag produces a positive visceral reaction for me, as I suspect it does for a lot of Americans. As with any nation’s flag, our flag is more than just the symbol of our country, it becomes a visual representation of our feelings of patriotism and love of home. Certain individual flags, in time of crisis, become a physical channel for our collective passions.

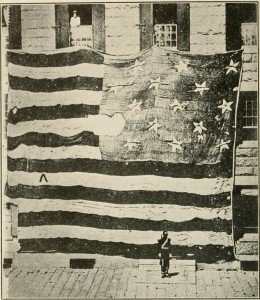

Ft. Sumter Flag:When the seven states of the deep South seceded following the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, Federal installations in the South were marooned. Most, such as Federal armories, were easily accessible to the Confederates and were quickly taken. A few Federal forts in and around Charleston Harbor, however, were isolated from land approaches and remained under Union control. The Union officer in charge, Major Robert Anderson, moved his garrison to Ft. Sumter, in Charleston Harbor, as hostilities became increasingly likely. After Major Anderson refused their ultimatum to evacuate, Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard gave the order, and the Confederates fired the first shots of the Civil War at Ft. Sumter on April 12, 1861. On the 14th, after some 34 hours of bombardment, out of food and with parts of the fort burning (but with no casualties), Major Anderson was compelled to surrender. He requested as part of his surrender terms permission to fire a 100-round salute to the flag which flew over the fort, which Beauregard granted. Unfortunately, a shell exploded prematurely on the 47th shot, killing one man and wounding another, and the salute was reduced to 50. After lowering the flag, the Union soldiers were allowed to simply board a ship for the North, taking their ensign with them.

Major Anderson was proclaimed a hero in the North, and he and the flag went on a fund-raising tour where the flag was “auctioned” off (and then promptly re-donated by the winner) again and again to raise funds for the nascent war effort. After the four bloodiest years of our history, with the South beaten, (now) Major General Anderson returned to Ft. Sumter with the same flag and raised it again over the fort. The dramatic flag-raising ceremony was on April 14, 1865, four years to the day after the fort’s surrender. Ironically, it was also the night Lincoln became the first U.S. President to be assassinated.

Iwo Jima Flag: One of the most iconic images of World War II (or any war, for that matter) was captured by photographer Joe Rosenthal at the height of one of the fiercest fights, the Battle for Iwo Jima. Four days after landing on Iwo Jima, amid terrible fighting, Marines of the 5th Division reached the top of Mt. Suribachi, the highest point on the island. Actually the second flag-raising on Mt. Suribachi that day (February 23, 1945), the moment captured on film was on the front page of newspapers across the country within 18 hours. President Franklin D. Roosevelt immediately saw its value in helping the war effort, and the inspiring image, along with the three survivors of the six soldiers who raised the flag, were soon on a tour to sell U.S. War Bonds. Roosevelt was right: the 7th Bond Tour raised an incredible $24 billion for the war effort, the largest borrowing from the American public in history. To put that amount in perspective, the entire budget of the U.S. Government in 1946 was $56 billion.

Ground Zero Flag: Out of the tragedy of the September 11, 2001 attacks came a new iconic image for a new generation: the sight of three dust-covered New York firefighters raising a flag on an improvised flag pole at Ground Zero, the site of the World Trade Center. Shot by Thomas E. Franklin of The Bergen Record, the resilience and defiance this photo conveys lifted our spirits even as we mourned the victims of that senseless act of terror. Shortly after the 9-11 Attacks, my son Michael, who was a Damage Controlman (firefighter) in the Navy, deployed on his ship the USS Theodore Roosevelt in support of Operation Enduring Freedom, the War on Afghanistan. Soon after the ship embarked, the Navy asked to borrow the Ground Zero Flag, and so New York City lent the flag to the Navy who forwarded it to the Theodore Roosevelt, then in the Arabian Sea supporting the air war in Afghanistan.

On September 30, 2001 a ceremony was conducted on board the Theodore Roosevelt wherein the Ground Zero Flag was presented to the Theodore Roosevelt firefighters. I’m proud to say that Michael was one of the firefighters to participate in that ceremony. On this deployment, the Theodore Roosevelt remained at sea for 159 consecutive days, longer than any warship since World War II. I remember Michael saying they worked 16 hours a day for 79 straight days before they got a day off. When the guys on the ground need air support, they need it now.

While participating in Operation Enduring Freedom, the Ground Zero Flag was flown from the Theodore Roosevelt’s halyards, an especially poignant reminder to the sailors and airmen what we were fighting for, and an especially “in-your-face” reminder to the Taliban what we were fighting for. At the end of Theodore Roosevelt’s deployment, the flag was formally transferred back to police and firefighters representing New York City. There’s a sad footnote to this story, however. In August 2002, New York City lent the flag back to the original owners prior to its transfer to the Smithsonian. To their dismay, the owners realized that the flag the city returned to them was not the flag taken from their yacht the Star of America and hoisted by the firefighters at Ground Zero. They have tried to force New York City to find the original flag, but so far have not met with success.

Vox’s Take: I think it’s a shame that the original Ground Zero Flag has been lost, just as it’s a shame part of the Star-Spangled Banner was cut up for souvenirs over 150 years ago. I hope the Ground Zero Flag can be found. Despite this, both flags have served their purpose, and the images they have given us, which can never be lost, are just as powerful as the actual artifacts.

Sources:

[1] Battle of Baltimore, United States History.com

[2] Star-Spangled Banner, National Museum of American History

[3] Battle of Fort Sumter, Wikipedia

[4] Oral History- Iwo Jima Flag Raising, Naval History & Heritage Command

[5] Battle for Iwo Jima, 1945, Navy Department Library

[6] Bond Tour, IwoJima.com

[7] Raising the Flag at Ground Zero, Wikipedia

[8] Operation Enduring Freedom, Wikipedia

[9] Help Find the Flag, findthe911flag.com