Polio: Ancient (and Modern) Scourge

I remember distinctly my first polio vaccine. Now usually it would be very unusual for me to remember getting a vaccination, but this was a special case. One day, about 1963 I’m thinking, my entire grade school class was taken to Gove Middle School in Denver, where sugar cubes containing a drop of the new oral polio vaccine were being given en masse to school children. This was because the much-anticipated polio vaccine was finally available in quantity, and a major health risk for children could now be effectively fought. It’s hard to imagine now, but in the first half of the 20th Century polio was one of the most feared diseases and the annual polio outbreaks were a common and dangerous occurrence.

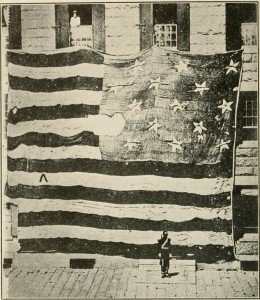

Pre-Vaccination

Pre-Vaccination

Polio (also known as poliomyelitis or infantile paralysis) is a highly contagious viral disease which has dogged the human race throughout its history. Polio was first described in 1789 by English physician Michael Underwood as a debility of the lower extremities in children. [1] Polio outbreaks were first reported in the United States in 1843. Polio did not, however, reach epidemic proportions until the industrial revolution and the concentration of people in cities. This was due to the normal transmission method of polio: people drinking contaminated water or eating contaminated food. In medical terms this is the fecal-oral route of disease transmission. (Eewww!) Cities were notoriously dirty in the early industrial age, with inadequate waste water disposal systems.

With the rise of the cities the number, scope and intensity of outbreaks gradually increased. In addition, increasingly older people were becoming sick with polio. For over a hundred years, the annual summer and fall outbreaks increased, until the U.S. reached a peak of polio cases in 1952. In that year, the U.S. incurred some 58,000 reported cases, with 3,145 deaths and 21,269 cases of paralytic polio. The real number of cases may actually have been much higher, since modern research indicates that only about 1% of polio cases result in paralysis. [2] The number of new cases began to drop after 1952 with improvements in sanitation and with municipalities banning public swimming venues upon news of an outbreak starting.

My mother-in-law Betty and her brother Jimmy were both inflicted with polio as children. Nana remembers being treated with Sister Kenny’s controversial treatment. [3] Sister Kenny developed her treatment of hot compresses and passive exercise from practical experience, and despite her success the technique was not accepted by many in the medical establishment of the day. Betty and Jimmy were spared the paralysis and pretty fully recovered, though Betty has one leg ½ an inch shorter than the other and Jimmy suffered from post-polio syndrome in his later years. My brother Marty remembers going over to one of his friend’s houses, whose polio-infected mother was not so lucky and was confined to an iron lung in the living room. The iron lung was necessary because the paralysis had affected the muscles of her chest, making breathing impossible without assistance.

The March of Dimes

The March of Dimes

The March of Dimes, originally known as the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, was founded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on January 3, 1938 in response to the increasingly severe polio outbreaks. [4] Roosevelt, himself diagnosed with polio, was unable to move his legs, a fact (though not secret) that was carefully de-emphasized throughout his political career. After Roosevelt’s death, the nation wanted to commemorate Roosevelt in many ways, including coinage. The U.S. Mint concluded that the dime was the obvious choice for honoring FDR. Interestingly, modern medical scholars think that Roosevelt may actually have had Guillain-Barré syndrome rather than polio.

Modern Times

The World Health Organization reports that the polio vaccine has been enormously successful in combating the spread of polio throughout the world, except in three countries: Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan. What’s going on there? Well, sadly there are many people in these countries who won’t get vaccinated, either because of rumors that the vaccine is harmful or because of pressure from Muslim extremists, who view the Polio Global Eradication Initiative as a Western conspiracy. In fact, on several occasions polio vaccination workers have been murdered [5] by these misdirected individuals.

Vox’s Take: There’s no good reason why polio could not join smallpox on the tragically short list of infectious diseases to be completely eradicated by medicine. [6] However, it cannot be eliminated until everyone cooperates, including the religious zealots.

Sources:

[1] Polio History, EMedTV

[2] Poliomyelitis, Wikipedia

[3] Sister Kenny: Confronting the Conventional in Polio Treatment, by Miki Fairley, Orthotics & Prosthetics.com

[4] January3, 1938: Franklin Roosevelt founds March of Dimes, This Day in History, History.com

[5] Gunmen Kill Nigerian Polio Vaccine Workers in Echo of Pakistan Attacks, By Donald G. McNeil Jr., The New York Times

[6] Pages in category “Eradicated diseases”, Wikipedia