Sinking of the Lusitania

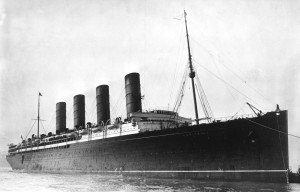

The RMS Lusitania, launched in 1907, was one of the fastest ocean liners of her time, holding the Blue Riband for fastest Atlantic passenger liner crossings along with her sister ship, the RMS Mauretania. With the help of state-of-the-art Parsons steam turbine engines generating 68,000 horsepower [1], fed by 25 boilers and turning four huge screws (propellers), she regularly cruised at 25 knots.

On May 7, 1915, during World War I, she was nearing the end of a crossing from New York to Liverpool. South of the coast of Ireland, her lookout saw a trail of foam rapidly approaching the ship and shouted “Torpedoes!”. There was just one torpedo, but it slammed into the starboard side and detonated. Moments later a huge secondary explosion rocked the ship. She sank in just 18 minutes amid a chaos of trying to launch lifeboats, killing 1,198 of the 1,959 people on board, including 128 Americans. [2]

The torpedo came from the German submarine U20. The sinking of the Lusitania outraged Americans and helped turn the national sentiment, which had been very isolationist and neutral regarding the great European war, decidedly against the Germans. The Lusitania incident contributed to America eventually entering the war on the side of Britain and France. Why would the Germans attack a passenger liner with innocent women and children on board? Was this a wanton case of barbarism, as the English news stories claimed?

As always, there is more to the story than this. Near the start of the war in August 1914, the British, wanting to leverage the might of the Royal Navy, imposed a blockade of German ports. This blockage was very effective, causing starvation in Germany and the eventual deaths of 763,000 civilians, according to official statistics [3]. Germany responded with the only advantage she had, which was her submarine service, the most advanced in the world. Germany declared the North Sea and the area around the British Isles a British “military area” and warned that any ships entering this area, including those from neutral countries, were subject to submarine attack. The British admiralty responded to this declaration with orders for a merchant ship who encounters a submarine to steer straight for it at utmost speed – in effect instructions to ram the small and vulnerable submarine. The “rules of war” up to this time called for warships intercepting merchant vessels to stop them and allow for passengers and crew to disembark before firing on the ship, unless the ship resisted, attempted to flee, or was part of a convoy. The Germans were aware of the British admiralty instructions and the extreme vulnerability of a submarine on the surface. In addition, a submarine with a surface speed of 15 knots could not possibly keep up with a fast liner like the Lusitania. In light of this, in February the German government announced that allied ships in the war zone would be sunk without warning.

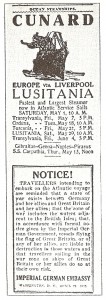

Most passengers were unaware of two crucial facts about the Lusitania. First, she was secretly subsidized by the British government, and in return was built to meet with specifications to allow her to be converted to an Armed Merchant Cruiser if the need arose. She had magazines for powder and ammunition, and gun mounts concealed underneath her decks. Second, on her final voyage she was carrying contraband (military cargo), including 4.3 million rounds of Remington .303 cartridges, used in both rifles and machine guns. Passengers were not aware of the contraband, but the Germans, via their spy network, almost certainly were. In fact, the German Embassy in Washington took out an ad in the New York newspapers, warning people not to book passage on the Lusitania. The German notice was printed next to a Cunard Line advertisement for the voyage, and caused a stir. Many people took heed, and the Lusitania was only at about half capacity on the final voyage.

All of these factors combined to a situation where the U20 issued no warning and simply fired a torpedo when the Lusitania came within range. The propaganda offices in both Britain and America were quick to portray the attack as a war crime. The Kaiser was quick to defend it. So the question for discussion is: was the commander of the U20 justified in this situation to fire on the Lusitania, or were the newspapers correct, and this was a barbaric act and a war crime?

Vox’s Take: War is a very difficult thing to conduct in a “civilized” manner. In the words of William T. Sherman, “War is cruelty and you cannot refine it.” [4] Certainly, it’s hard to see how the sinking of a passenger liner loaded with civilians is justified. But did the Germans, with their people starving, have a right to enforce their own blockade in the manner they could, as the British were doing? And what did the Brits intend to do with the 4.3 million rounds of ammunition? Why, shoot them at the Germans of course. It can be argued that the Germans did indeed give warning, not on the high seas but before the voyage even began. My take is that the sinking was not “civilized”, but was not a war crime, given the conditions in which it occurred. What’s your take?

Sources:

[1] The Sinking of the Lusitania, Eyewitness to History

[2] RMS Lusitania, Wikipedia

[3] The blockade of Germany, Spotlights on history, National Archives

[4] Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, AmericanCivilWar.com