The Last U.S. Cavalry Charge

You are all familiar, I’m sure, with the image of the horse-mounted Cavalry from movie Westerns. Care to guess in which war the last United States horse-mounted cavalry charge took place?

o Civil War (1861-1865)

o Spanish-American War (1898)

o World War I (1914-1919)

o World War II (1939-1945)

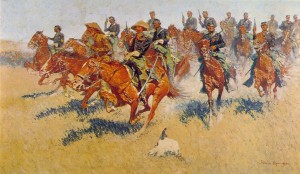

The answer may surprise you: it was during World War II. It happened January 16, 1942 near the village of Morong on the Bataan Peninsula, during the Japanese invasion of the Philippines, when the U.S. Army’s 26th Cavalry surprised a Japanese infantry unit and scattered them. [1] A nice painting commemorating the charge can be viewed here. But didn’t they have tanks and jeeps and half-tracks in World War II? Sure they did, but while the Army began the process of mechanization during World War I, this process was not complete even at the start of World War II. There was still a little room for an old-fashioned cavalry charge. The U.S. example, by the way, is not the last in history. As with a lot of historical trivia, there’s a lively debate over when the last cavalry charge in the world actually took place.

The traditional mission of the cavalry was as a specialized scouting and quick assault force. Military commanders used the cavalry to find the enemy’s forces, screen the enemy from finding their own forces, and strike the enemy at focused points in a battle. This is not to be confused with the use of horses as a means of military transportation. Dragoons, or mounted infantry, use horses to get to the scene, but any fighting is done while dismounted. As the photo shows, there are some pretty recent examples of the military use of horses – such as U.S. Special Forces during Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan in 2006. Sometimes the terrain just isn’t suited to mechanized vehicles, as anyone who has hiked in the Rockies can attest.

Sources:

[1] The Last Mounted Cavalry Charge: Luzon 1942, The CBS Interactive Business Network

[2] Cavalry, Wikipedia