Harriett Beecher Stowe

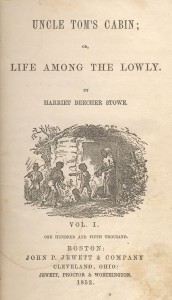

The best-selling novel of the 19th Century, and the second best-selling book in that century after the Christian Bible, is Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe. This sentimental anti-slavery novel is an early example of using literature to affect social change. The book was published in 1852, as the nation was beginning to experience significant problems with the “Compromise of 1850”, that series of legislative acts which attempted once more to reconcile the irreconcilable differences between North and South over slavery. [1] Stowe, an active abolitionist born in Connecticut, wrote the book in response to the most abhorrent (to abolitionists) part of the compromise – The Fugitive Slave Act. Her immediate objective was to raise doubts about the Southern portrayal of slavery as a necessary and just institution. The book is listed among the most influential books of all time, among such titles as The Illiad and The Communist Manifesto. [2] It was as popular in Britain as the (Northern) United States, and was translated into all major languages. As you might guess, it was virulently despised in the South. In its time it was widely viewed as a stepping stone on our inexorable path to Civil War, and an urban myth says that Abraham Lincoln, when meeting Stowe in 1862, quipped “So this is the little lady who started this great war”. [3]

Cover of Uncle Tom's Cabin

While it is certain that

Uncle Tom’s Cabin had a positive social impact in terms of shifting Northern attitudes more strongly against slavery (and possibly helping secure Lincoln’s election in 1860), the book is viewed today with mixed feelings. This is because it inadvertently helped create a number of stereotypes about blacks, some of which persist today. These include the

“Uncle Tom” stereotype of the long-suffering but loyal black man who is devoted to his white master, and the

“Mammy” archetype of the loud and overweight but good-natured black nanny.

Vox’s Take: From our 21st Century viewpoint, it may be hard to understand how deeply racist our country has been throughout our history, and that for much of that history it was a social norm, not an individual’s character defect. We tend to think that a person such as an abolitionist, who was passionately opposed to slavery, was automatically a believer in racial equality. But that’s not how folks thought back then – views were much more complex than that. There were believers in racial equality at the time of the Civil War, but this viewpoint was radical and on the fringe. The great majority of people, even those opposed to slavery, took it for granted that the black race was inferior to the white. Those beliefs, widespread and entrenched as they were, took a long time to change. That’s part of why there’s 99 years between the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery in 1865 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which finally began to codify equality in the law.

Sources:

[1] Compromise of 1850, Library of Congress

[2] The Most Influential Books in History, goodreads.com

[3] Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Wikipedia