The Great Fire(s) of October 8, 1871

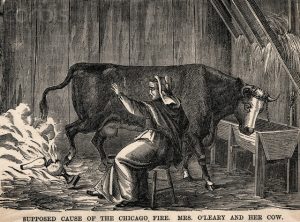

The night of Sunday, October 8, 1871 saw a huge, destructive fire rage through the city of Chicago, Illinois. The Great Chicago Fire started in the barn of one very unfortunate Mrs. Patrick O’Leary on the corner of DeKoven and Twelfth Streets. The fire raged to the northeast, eventually consuming some 2,000 acres and 17,000 buildings of Chicago, killing 300 people and leaving 100,000 people – a third of the city’s population – homeless. [1]

That fire is not the subject of this article, for it was only the second-worst (perhaps even third-worst) fire of that terrible evening in loss of life.

Who’s Heard of Peshtigo, WI?

The greatest fire in terms of loss of life happened that same night in Peshtigo, Wisconsin and surrounding areas. The Great Peshtigo Fire of 1871 resulted in the deaths of between 1,200 and 2,500 people (800 in Peshtigo alone), and is the deadliest fire in U.S. History. [2] Because the fire was mainly rural, it is called a forest fire in many sources. Fires had actually been burning in the Peshtigo area for weeks, but due to extremely hot and windy conditions Sunday night, these merged and grew into a firestorm which engulfed Peshtigo on October 8. The Peshtigo fire scorched about 1.2 million acres of land, and actually jumped Green Bay to burn parts of Door and Kewaunee counties on the Door Peninsula.

The poor people of Peshtigo and neighboring towns did not know the danger they were in until a wall of fire raced towards the town. We get a glimpse of the horror of that night in this newspaper article from October 11th:

From the survivors, we glean the following in reference to the scene at the village and in the farming region commonly known as the “Sugar Bush.” Sunday evening, after church, for about half an hour a death like stillness hung over the doomed town. The smoke from the fires in the region around, was so thick as to be stifling and hung like a funeral pall over everything and all was enveloped in Egyptian darkness. Soon, light puffs of air were felt, the horizon at the south east, south and south west began to be faintly illuminated, a perceptible trembling of the earth was felt, and a distant roar broke the awful silence. People began to fear that some awful calamity was impending, but as yet, no one even dreamed of the danger.

The illumination soon became intensified into a fierce lurid glare, the roar deepened into a howl, as if all the demons from the infernal pit had been let loose, when the advance gusts of wind from the main body of the tornado struck.

Chimneys were blown down, houses were unroofed, the roof of the Wooden Ware Factory was lifted, a large ware house filled with tubs, pails, [kanakans?], keelers and fish kits was nearly demolished, and amid the confusion terror and terrible apprehension of the moment, the firey element in tremendous unrolling billows and masses of sheeted flame, enveloped the [doomed?] village. The frenzy of despair seized on all hearts, strong men bowed like reeds before the firey blast, women and children, like frightened spectres flitting through the awful gloom, were swept like Autumn leaves. Crowds pushed for the bridge, but the bridge, like all else, was receiving its baptism of fire. Hundreds crowded into the river, cattle plunged in with them, and being huddled together in the general confusion of the moment, many who had taken to the water to avoid the flames were drowned. A great many were on the blazing bridge when it fell. The debris from the burning town was hurled over and on the heads of those who were in the water, killing many and maiming others so that they gave up to despair and sank to a watery grave.

In less than an hour from the time the tornado struck the town, the village of Peshtigo was annihilated! [3]

The firestorm that destroyed Peshtigo has been compared to the man-made firestorms of World War II which decimated Dresden and Tokyo. Like those cities, there was nowhere to hide from the advancing wall of flame:

People didn’t just die in Peshtigo. They spontaneously combusted and were cremated by heat that reached 2000 degrees. They succumbed instantly from breathing in poisoned, superheated air. They died of smoke inhalation, were run over by panicked livestock and drowned in the river where they sought refuge. Others were crushed in collapsing buildings, impaled by flying debris and pulverized by all kinds of things dropping out of the sky on top of them. Still others committed suicide rather than face death by fire. There is one known case where a father killed his three daughters and then himself to avoid that fate. [4]

The same hot and windy conditions that fanned the flames of the Chicago and Peshtigo fires also resulted in The Great Michigan Fire, which burned several towns in the thumb of Michigan and may itself have resulted in over 500 deaths, placing Chicago third on the list of fatal fires that night. [5]

1871 illustration from Harper’s Magazine depicting a shocked Mrs. O’Leary seeing her cow kicking over the lantern while she is milking. [6]

Vox’s Take: You should know that a newspaper reporter admitted to making up the story of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow starting the Chicago fire. Even though the story was debunked almost immediately, it has survived all these years – some sources still casually cite the actions of this supposed bovine arsonist as fact.

The newspaper article quoted above conveyed better than I could the horrific situations these people experienced.

Sources:

[1] What (or Who) Caused the Great Chicago Fire?, SMITHSONIAN.COM

[2] List of disasters in the United States by death toll, wikipedia.org

[3] The Great Peshtigo Fire of 1871, Deana C. Hipke. The Great Peshtigo Fire of 1871.

[4] Peshtigo Fire, Peshtigo, WI, exploringoffthebeatenpath.com

[5] The Great Midwest Wildfires of 1871, National Weather Service

[6] Catherine O’Leary, wikipedia.org