I would make a bet that if you took a poll, asking the average Joe what is the worst U.S. maritime disaster, you would get “The Sinking of the Titanic” as the number one answer. I would agree that the RMS Titanic is by far the most famous, but it was not really a U.S. disaster, and not the worst in terms of loss of life (in U.S. History). That grim distinction belongs to the explosion and subsequent sinking on April 27, 1865 of the SS Sultana, a Mississippi River steamboat paddlewheeler.

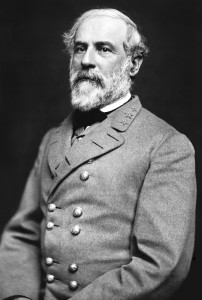

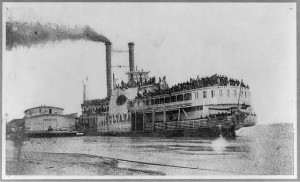

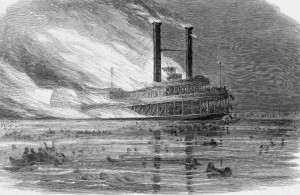

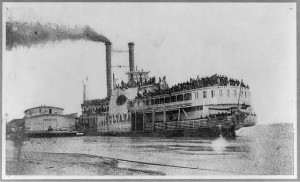

SS Sultana on April 26, 1865

The Sultana was a new, state-of-the-art steamboat, built in 1863. She had been making regular runs up and down the Mississippi from St. Louis to New Orleans during the last two years of the Civil War. On her last trip, she was commissioned by the Federal Government to carry Union solders upriver, on their way home as the war came to a close. In fact, most of the passengers were newly released prisoners of war, from the Cahaba and Andersonville prisons.

The high death toll was due to the fact that the ship was dangerously overloaded. She was by law limited to 376 passengers and crew. However, there were thousands of former Union prisoners at Vicksburg, Mississippi, anxious to take the first available ship and get home. The government was paying a lucrative $5 per soldier to get them home, so the ship’s captain, J. C. Mason of St. Louis, was incented to put as many passengers on board as possible. According to some, the military officers were being paid a kickback of $1.15 per person to look the other way and ignore the overcrowding. [2] At any rate, the Sultana was carrying 2,200 to 2,400 people at the time of the disaster, six times the legal limit. So many people were crammed on board they decided not to make out a passenger list. As you can see from the photo taken the day before she sank, the Sultana was packed with people literally shoulder-to-shoulder. Extra stanchions were installed to support the hurricane (top) deck, which was sagging from the weight of the passengers.

At Vicksburg, the engineers discovered leaks and a bulge in one of the boilers. Not wanting to lose time and take a chance on another steamboat getting the opportunity to carry the passengers, the captain decided to patch the boiler rather than replace it, which would have taken three days.

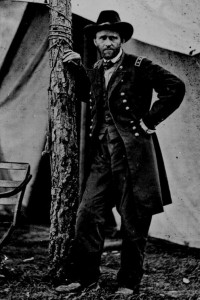

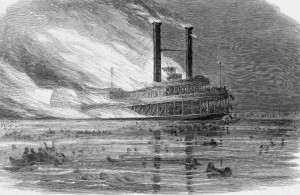

Sultana Burning, Harper's Weekly

The Disaster: After stopping in Memphis, Tennessee, Sultana started upriver, headed for the next stop at Cairo, Illinois, where most of the passengers were scheduled to disembark. The spring runoff was underway, so the river was high and the current strong, which meant that the Sultana needed a higher than normal head of steam to make her way upstream. The steamboat, top-heavy from too many passengers, was careening from one side to the other. At 2:00 a.m. on the 27th, about seven miles upriver from Memphis, three of the four boilers exploded. The explosion tore a gaping hole in the Sultana and sent burning pieces of coal flying everywhere, which quickly caught the wooden ship on fire. Men were blown off the ship, or jumped into the icy spring water to escape the flames. Soldiers drowned, burned, died from hypothermia, or were crushed when the smokestacks collapsed onto the stricken ship. About 500 men were rescued from the water, of which some 200 to 300 died later from burns, hypothermia, or their general poor health resulting from their captivity. Altogether some 1,700 to 1,800 people died, making it the worst maritime disaster in American History.

The Cause: The explosion was likely caused by four factors: the steam pressure was probably abnormally high due to the need for extra power to overcome the strong current. The hasty boiler repairs were inadequate to insure safety. The careening could also have played a part – the four interconnected boilers were arranged side-by-side, which meant that water could flow from the highest boiler to the lowest as the ship tilted to one side then the other. If the water level was not properly maintained, hot spots could develop, where the iron boilers become red-hot due to lack of water, then when the water rushes back it would instantly turn to steam, causing a sudden surge in the overall steam pressure.

Coal Torpedo

Sabotage? Another possible cause for the boiler explosion was reported in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in an article on May 6, 1888. [4] In this article, William C. Streetor, a resident of St. Louis, reported that while he worked as a clerk and assistant keeper in the Gratiot and Myrtle street prisons, an ex-Confederate Secret Service agent and boat-burner, Robert Louden (or Lowden), claimed he had smuggled a coal torpedo aboard the Sultana at Memphis. The coal torpedo was a small explosive device made to look like an ordinary lump of coal, but would explode in a coal furnace, causing a secondary explosion of the boiler. (During the Civil War, a broad variety of explosive devices were called “torpedoes”.) Some sixty Union steamboats were destroyed by Confederate agents during the war. [5] The sabotage theory was called “wholly baseless” in one source [2], and given credibility in others. [5]

Why is the Sultana Disaster unknown? When the Sultana’s boilers burst, the nation was inundated with news. Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated, and John Wilkes Booth had been caught and killed on April 26th, the day before the Sultana exploded. Also on the 26th, the last major Confederate Army, under Joseph E. Johnston, surrendered to William T. Sherman. Possibly because of the shady nature of the circumstances around the overcrowding, the Army was not anxious to publicize the story. The public was either tired or desensitized to news of death, having just gone through a war in which at least 618,000 soldiers were killed. Finally, anything which happened in the West received less coverage in Eastern papers.

Vox’s Take: Whether the sinking of the Sultana was accidental or deliberate, it was an especially tragic end for the Union prisoners of war who survived incredible deprivation in Southern prison camps, only to be killed when they were so close to getting home. In a small way, the incident helped bring former enemies together: the people of Memphis cared for the survivors and raised funds to help them. [3] One ex-Confederate soldier in a small boat is said to have single-handedly rescued fifteen Union survivors. [2] Perhaps someday this incredible story will find its way into the history books. Interestingly enough, the remains of the Sultana may have been found in 1982, 32 feet under a soybean field in Arkansas. [3] The Mississippi River has changed course many times, and the wreckage is now two miles from the current location of the main channel.

Sources:

[1] Remembering Sultana, National Geographic News

[2] Death on the Dark River, The Story of the Sultana Disaster in 1865, ancestry.com

[3] SS Sultana, Wikipedia

[4] Sabotage of the Sultana, Civil War St. Louis

[5] The Boat-Burners, Civil War St. Louis