(To see all the posts in this series, click here: Naval Armor.)

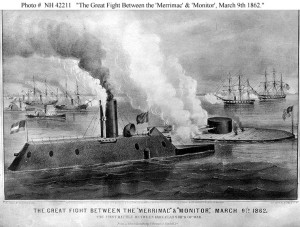

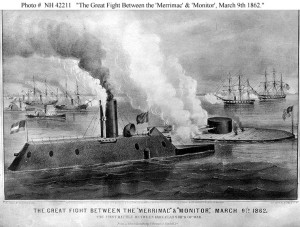

The birth of “modern” naval warfare is sometimes traced to the first engagement between two ships protected by iron armor – the “ironclads”. The Battle of Hampton Roads, more famously referred to as the Battle of the Monitor and the Merrimac, occurred on March 8-9, 1862 during the U.S. Civil War.

CSS Virginia

The

USS Merrimac was a wooden-hulled screw frigate launched by the U.S. Navy in 1855. She was in port, due for an engine overhaul at the outbreak of war on April 12, 1861. When the Gosport Navy Yard (later Norfolk Navy Yard) was in danger of being overrun on April 20 by Confederate land forces, the Navy set fire to and scuttled her before abandoning the yard. The

Merrimac sank in shallow water without burning completely. The Confederates, desperate for ships, were able to salvage the hulk. Afraid that the North was planning a fleet of ironclads, they decided to rebuild her as an ironclad ram. She was fitted with a four-inch thick iron deck and a sloping casemate (fortified enclosure or roof) of two two-inch plates of railroad iron backed by 24 inches of pine and oak. They mounted ten guns (cannons) on her, four along each side and one swiveling gun each for the bow and stern. Finally, she was fitted with an eight-foot long, 1,500 pound iron ram at her bow. They renamed the rebuilt ship the

CSS Virginia. The additional weight was almost too much for the

Virginia, whose keel was of course not designed for it. The Virginia also had to make do with the original steam engines meant for the much lighter

Merrimac, and so she was woefully underpowered and slow. The additional weight also caused her to draft deeper than before at up to 22 feet, limiting her use in rivers and coastal waters. She was top-heavy, and between the underpowered engines and deep draft she was ”little more manageable than a timber-raft” – she required 45 minutes to turn a complete circle. She wasn’t fit for the open ocean either, so her prospects seemed iffy. In fact, some Confederate newspapers had already pronounced her a failure before her first battle.

USS Monitor

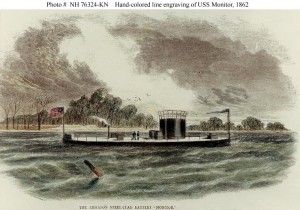

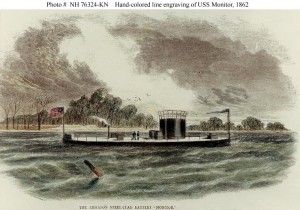

The North did not actually have plans in motion to build an ironclad, but they heard about the new ironclad being built by the Confederates, and so embarked on a crash program to produce an ironclad of their own. The Navy employed Swedish engineer John Ericsson who came up with a radical new design. The

USS Monitor featured just two large-caliber (11 inch) Dahlgren guns, but these were mounted in a swiveling turret so they could fire in any direction. Most of the ship lay under the water line beneath a flat deck of one inch armor supported by heavy timbers. Her sides had five inch-thick iron plates, backed by oak. The turret was comprised of eight layers of one inch iron plate, bolted together. A ninth plate inside acted as a sound shield. This new style of ship was like nothing anyone had seen before. One Confederate officer thought she looked like a “cheese-box on a raft”. The

Monitor had a very modest seven to eight foot draft, making her very suitable for rivers and shallow coastal waters. Like the

Virginia, the

Monitor was not fit for the open ocean – with the armored turret she was top-heavy, and with the shallow draft she was vulnerable in rough seas.

Battle of Hampton Roads

On March 8, 1862, the

Virginia was supposed to go out on sea trials, but the captain instead decided to contest the Federal blockade of the waters around Norfolk and Newport News, Virginia – a body of water called Hampton Roads. The wooden Federal fleet saw an approaching ship that looked like a “barn roof” and soon realized that they were up against the rumored Confederate ironclad. They joined in battle, but they were completely outclassed. The shells from the Union guns simply bounced off

Virginia’s sloping iron casemate. Ignoring a small union gunboat,

Virginia first attacked and sank the

USS Cumberland by ramming her below the water line. The ram became stuck in

Cumberland’s hull and nearly dragged the

Virginia down with the

Cumberland, but then the ram broke off and

Virginia backed away. The

Cumberland died fighting, firing her guns as long as they were above water.

Next,

Virginia engaged the

USS Congress. After an hour, the

Congress was badly damaged and surrendered. At this point a Union shore battery fired on the

Virginia and she retaliated by firing “hot shot” (cannon shot heated red-hot) at the

Congress, which caught fire and burned the rest of the day. The

Virginia then tried to engage the

USS Minnesota, which had run aground in shallow water. But because of her deep draft, the

Virginia was not able to get within range. The battle was suspended when

Virginia’s captain became concerned they would miss the high tide and not be able to make it over a sand bar and back to port.

At dawn the next day, March 9,

Virginia returned to finish off the

Minnesota. During the night, however, the Federals had managed to reach the scene of battle with the new

USS Monitor. As the

Virginia approached the

Minnesota, the

Monitor interceded. The resulting engagement lasted most of the day, with the

Monitor and the

Virginia pounding each other, often at point-blank range, with little effect. Despite their other flaws, each ship’s armor was very effective against the other’s shells. At one point the

Virginia tried to ram the smaller

Monitor, but without her iron ram this tactic failed. At the end, the

Monitor and the

Virginia disengaged, each thinking the other was quitting, and each claiming victory.

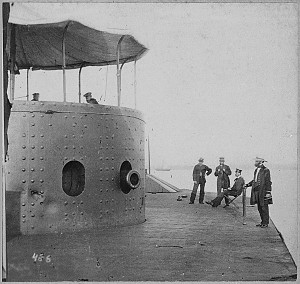

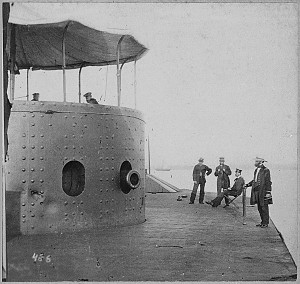

Turret of the Monitor, dented by shells

You know how some innovations can go for decades before they catch the world’s attention? That’s not the case here. News of the “Battle of the Ironclads” sent a shock wave through the navies of the world, as everyone recognized immediately that wooden-hulled ships were hopelessly obsolete compared to the ironclads. The revolving turret was also an extremely important innovation, because for the first time you did not have to position the whole ship in order to bring your guns to bear on an opponent. This made the

Monitor, not the

Virginia, the model for future warship development.

Neither ship fought again, and neither survived the year. In May, the

Virginia was ordered blown up by her own Navy in order to avoid capture, and in December the

Monitor foundered and sank in rough seas. However, their one battle changed the course of naval warfare as radically as the switch from sails to steam.

Sources:

[1] Battle_of_Hampton_Roads, Wikipedia

[2] The Battle of the Ironclads, CivilWarHome.com

[3] USS Monitor (1862-1862), Naval Historical Center

[4] National Archives