Why Clocks Say “IIII’ Rather Than “IV”

You may have noticed – or you may not have. Take a look at a clock face with Roman-style numerals. Most of them show four as “IIII” rather than “IV”. What’s up with that? We were taught in grade school (at least I was) the subtractive notation for Roman Numerals: when you count higher than three or eight you can subtract one from the next highest five or ten and save yourself a numeral. So why don’t clocks do this? Rather, why do they do this for nine but not four?

Theory One has it that the heavy strokes of “IIII” aesthetically balance out the “VIII” on the other side of the clock, but that theory ignores that “V” does not balance out “VII”, and also ignores the fact that “IIII” was used on the very earliest clocks, which use a 24-hour face.

Theory Two is that clock-makers spelled four as “IIII” because it was more economical: you could cast all the characters needed for a clock face with four “X”s, four “V”s and twenty “I”s. Nice and symmetrical. But this theory ignores the fact that most clocks with cast numerals had the whole number cast as one piece, not as individual characters. Another problem with this theory is that there does not seem to be a decline in the use of “IIII” for clocks with painted faces. And finally, the “IV” saves you three “I”s for a “V”, so that should be more economical.

Theory Three has it that the tradition originated with Roman sundials, and “IIII” was easier for peasants to understand than the use of the subtractive “IV” (this theory relies on the supposition that poor people must also be stupid). Another problem with this theory is that old sundials use “IX” for nine. What? Peasants could figure out nine but not four?

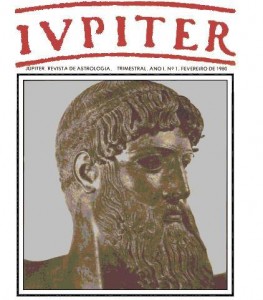

The “Right” Theory – I’m inclined to believe the practice originated something like this: clocks spell the Roman four as “IIII” because that was the common practice in all writings using Roman numbers at the time clocks were invented, around the 13th century. To be sure, the use of subtractive notation was in use at the time, e.g. nine was always “IX”, not “VIIII”, but four was an exception. Why is this? The theory is that “IV” was simply inappropriate for Romans to use for a number, because it was the first two letters, and consequently abbreviation, for “IVPITER”, the Latin script spelling for the god Jupiter. Jupiter was not just any god, he was the king of the gods. So out of respect for Jupiter or perhaps just to avoid misunderstanding, four had to be “IIII”. I first read about this theory in an article by Isaac Asimov some 30 years ago, in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, if I remember correctly. If the theory was good enough for Isaac Asimov, by golly, it’s good enough for me. The real answer may be lost to history, but it’s certainly a fun little anomaly to guess about.

Sources:

[1] FAQ: Roman IIII vs. IV on Clock Dials, UBR, Inc.

[2] Why does a clock face have ‘4’ as ‘IIII’ instead of ‘IV’ ?Askville by Amazon, Askville by Amazon

[3] CLOCKING THE FOURS: A NEW THEORY ABOUT IIII, Paul Lewis Post

[4] Time is racing, www.24hourtime.info