The Perfect Swarm

Have you ever heard of the Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus)? Mid-western farmers in the 19th Century sure knew of it. Every 7 to 12 years, this normally benign grasshopper entered a gregarious (swarming) phase and became a locust, and what swarms they made! The largest recorded concentration of animals ever, according to The Guinness Book of Records, was a swarm of Rocky Mountain Locusts. [1]

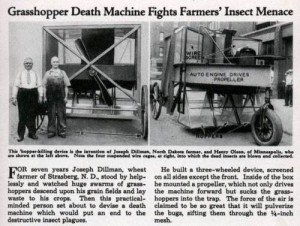

The swarm was observed by Dr. Albert Child of the U.S. Signal Corps in 1875, remembered by midwest farmers as the Year of the Locust. From timing the swarm as it passed overhead for five days, and telegraphing associates in other towns, Dr. Child estimated the size of the swarm as 1,800 miles long and at least 110 miles wide: 198,000 square miles containing 3.5 trillion grasshoppers! [2] Swarms of locusts, though not usually this size, descended on farming communities from Texas to Minnesota like a Biblical plague, eating every green thing in sight. When the plants were gone, the hungry insects ate leather, cotton and wool (still on the sheep). Housewives vainly placed blankets over their gardens. The pests ate the blankets, then the gardens.

Brief extracts from contemporary accounts will suggest the nature of the locust plague: “They came like a driving snow in winter, filling the air, covering the earth, the buildings, the shocks of grain and everything.” “Their alighting sounded like a continuous hailstorm. The noise was like suppressed distant thunder or a train in motion.” “They were four to six inches deep on the ground and continued to alight for hours. Their weight broke off large tree limbs.” “By dark there wasn’t a stalk of field corn over a foot high. Onions were eaten down to the very roots. They gnawed the handles of farm tools and the harness on horses or hanging in the barn, the bark of trees, clothing and curtains of homes and dead animals — including dead locusts.” [3]

A swarm of locusts devastates the family farm in Laura Ingalls Wilder‘s book On the Banks of Plum Creek. After this biological tsunami passed through, the crops were devastated and the settlers faced starvation, forcing the Federal and state governments to supply the stricken pioneers with food, clothing and seed for replanting crops.

Persons in the East have often smiled incredulously at our statements that the locusts often impeded the trains on the western railroads. Yet such was by no means an infrequent occurrence in 1874 and 1875-the insects pawing over the track or basking thereon so numerously that the oil from their crushed bodies reduced the traction so as to actually stop the train, especially on an up-grade. – Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture For The Year 1877. Washington, DC 1878. [7]

So why don’t you hear about these critters now? Because, in the space of 27 years, the Rocky Mountain Locust population went from an estimated 15 trillion to… zero. Nada. Extinct. The last known pair was collected in 1902, and is now at the Smithsonian Institution. The species was declared extinct in the 1950’s. How can such a thing happen? Just as “being smart is no guarantee against being dead wrong” – Carl Sagan, it turns out that large numbers are no guarantee against a spectacular decline.

Vox’s Take: Accidental demise or not, the story of the Rocky Mountain Locust is a cautionary tale we should heed. Life on this third rock from the Sun can be more fragile than is commonly supposed.

Sources:

[1] Rocky Mountain Locust, Wikipedia

[2] Six-Legged Teachers: Lessons from Locusts and Beetles, by Jeffrey A. Lockwood, WyoFile

[3] A Plague of Locusts, by Gerry Rising, August 1, 2004 issue of The Buffalo Sunday News

[4] Albert’s swarm, Wikipedia

[5] Looking Back at the Days of the Locust, By Carol Kaesuk Yoon, April 23, 2002 issue of The New York Times

[6] The death of the Super Hopper, by Jeffrey Lockwood, High Country News

[7] When The Skies Turned To Black: The Locust Plaque of 1875, Hearthstone Legacy Publications