Bell and the Telephone Controversy

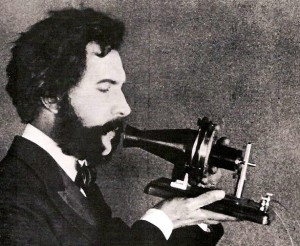

Every schoolkid knows that Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone. Right? Well, not according to some. You see, there has been a controversy about who invented the telephone, right from the very beginning. There are actually several claimants. In this post we’ll consider the main controversy, between Bell and Elisha Gray, co-founder of the Western Electric Manufacturing Company.

A little background is in order here. The demonstration of the telegraph by Samuel F.B. Morse in 1844 proved the ability to transmit electronic signals over long distances, even across the Atlantic. It wasn’t too much of a conceptual stretch to consider transmitting sounds over telegraph wires, and many people began working on the idea.

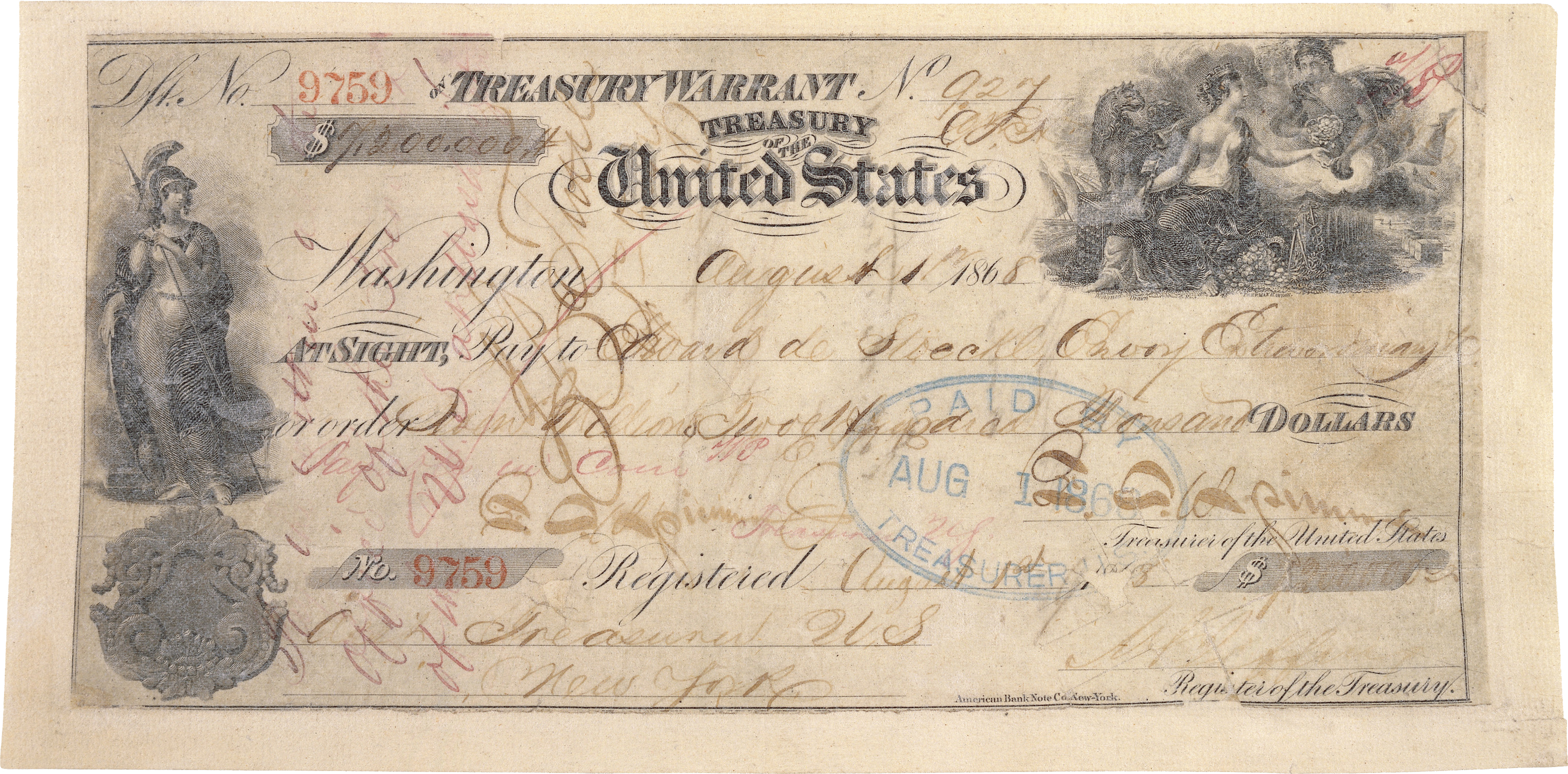

What is more interesting is that the patent examiner, Zenas Fisk Wilber, was a war buddy of Marcellus Bailey and owed him money. Wilber testified later that, contrary to Patent Office rules, he showed Bailey Gray’s patent caveat and discussed technical details of it, in particular the idea for a water transmitter for electrically reproducing sound. Wilber also stated that he showed the caveat to Bell himself, and that Bell gave him $100. Bell denied the $100 bribe, but does admit that he and Wilber talked about Gray’s caveat “in general terms”. To add fuel to the controversy, Bell’s patent drawings do not show a transmitter, but the narrative discusses a water transmitter in seven sentences which were “added at the last moment”.

Neither Bell nor Gray had a working prototype on February 14. Wilber, the examiner, did have doubts about Bell’s application and held up Bell’s patent application. Bell met with Wilber to answer questions about the application and satisfy him that Bell’s application was genuine. Wilber was satisfied, and Bell was awarded the patent, number 174,465, on March 7, 1876. Three days later, on March 10, Bell was working with his assistant Thomas Watson, using a water transmitter as a proof of concept. Bell spilled some acid while Watson was in another room and uttered the famous words into his new device “Mr. Watson – come here – I want to see you.” This was the first successful transmission of speech electronically. Bell did not continue using the water transmitter (it was impractical for production purposes) and by the time he first demonstrated the telephone publicly at the Centennial Exhibition three months later, in June 1876, he was using an electromagnetic transmitter of his own design. Bell made many public demonstrations in 1876 and 1877, proving that the telephone could transmit speech over long distances.

In late 1877 Gray, after allowing his caveat to expire, challenged Bell’s patent on the grounds that the water transmitter was his idea, not Bell’s. The Patent Office ruled that, while the water transmitter was undoubtedly Gray’s idea, Gray’s failure to take any action until Bell had conclusively proved the utility of the invention deprived him of the right to have his claim considered. Further litigation from Gray and others followed, an astonishing 600 lawsuits in the first 18 years of the Bell Telephone Company’s existence, but Bell’s patent held every time. Thus it was that Bell won the patent controversy and became the father of the telephone, and it’s his name that is known to every schoolkid.

Vox’s Take: It seems to me likely that Bell did indeed “borrow” from Gray’s water transmitter design, at least for a little while as he struggled to get his contraption working. Bell’s dependence on Grays’ water transmitter was short-lived, and he was past it before any public exhibition, but there it was nonetheless and it helped him get past a crucial stage in his efforts. Regardless of the legal implications, I think that Gray should at least be mentioned as a contributor to the invention of the telephone, vs. textbooks giving the impression that Bell was the only person thinking about this marvelous invention and that he came up the design completely on his own. What’s your take?

P.S. The U.S. House of Representatives passed House Resolution 269 in 2002, claiming that it is neither Bell nor Gray, but an Italian-American named Antonio Meucci who should be credited with the invention of the telephone. This resolution, coincidentally introduced by an Italian-American, Rep. Vito Fossella, is just the latest in what appears to be an unsolvable debate.

Sources:

[1] Who is credited as inventing the telephone?, Library of Congress

[2] Elisha Gray – The Race to Patent the Telephone, about.com Inventors

[3] Elisha Gray and Alexander Bell telephone controversy, Wikipedia

[4] News Flash: U.S. House of Representatives Says Alexander Graham Bell Did Not Invent the Telephone, History News Network